Alag Alag: Divorce in Hindi cinema

In Bollywood movies, divorce has been caused because of dogs, career ambitions, meddlesome parivaar, or more predictably, an extramarital affair.

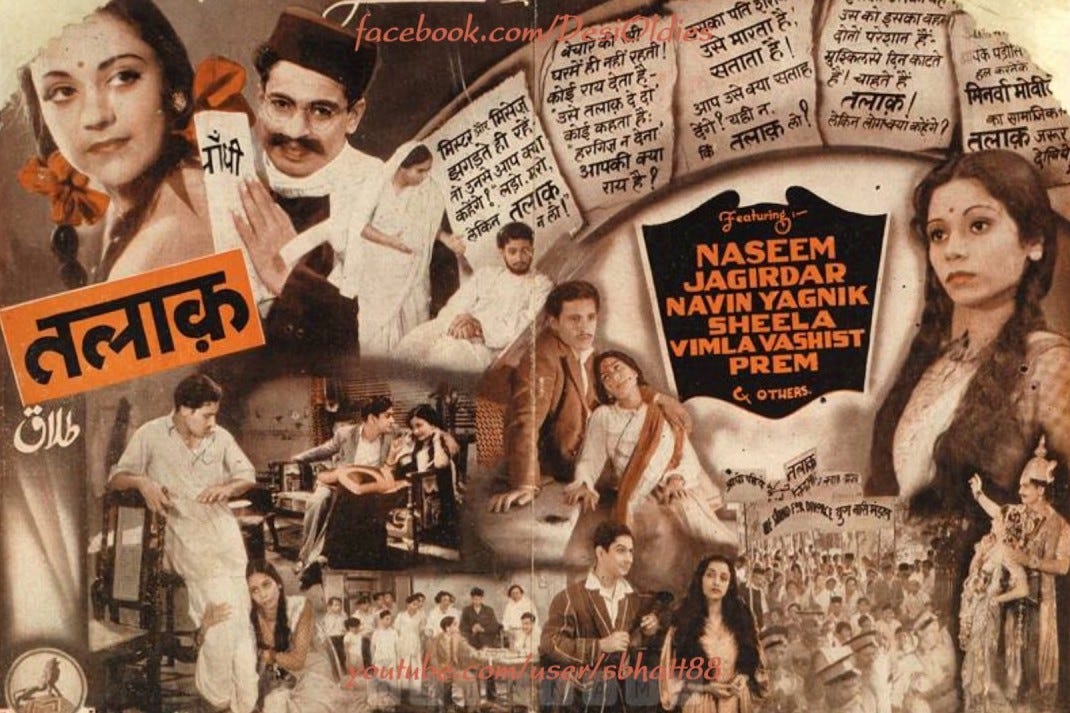

In 1938, Sohrab Modi’s Minerva Movietone made Divorce/Talaq, a social drama centred around divorce laws for Hindu women. One of the most popular stars of the era, Naseem Banu played the protagonist, Roopa. In order to separate from her husband, she leads a crusade for a law granting divorce to Hindu women—nonexistent until then. Though not much information is available about the film, according to a review in the February 1939 issue of FilmIndia magazine, Roopa ends her marriage “over a dog.” She remarries a film star who uses the same law to separate from her. Divorce did a balancing act around the subject. It highlighted the necessity of such laws for those stuck in bad marriages. Yet it built its story line around the argument that the law would be trivialised by the likes of Roopa seeking legal separation on insubstantial grounds and thus weakening the institution of marriage.

Much like Indian society, Hindi cinema has frowned upon the subject of divorce. It has been analysed in all kinds of ways—judgy, progressive, empathetic, even cautionary—but is far from normalised. The highly debated Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 inspired Guru Dutt’s classic romcom Mr & Mrs 55 down to its title. Despite its young, urban, and breezy look, it’s a rather conservative film with a skewed view of women’s liberation. The so-called “Divorce Bill” is seen as a tool wielded by misandrist women’s rights activists like the heroine’s crabby aunt, who feels like a caricature drawn by the film’s cartoonist hero. After a series of misunderstandings, the newlyweds realise their folly and drop the idea of splitting up. Though not before the heroine finally recognises a woman’s traditional role in domesticity.

Made three years later, Mahesh Kaul’s Talaq examines the ramifications of the breakdown of a marriage on a child’s psyche. He finds himself torn between his father and mother’s ego clashes as they prepare for legal separation. Even though the film holds both partners responsible for making a marriage work, it’s not done without suggesting the woman needs to be the peacemaker. Nanhi umar ki kaliyon, tumko dekh rahi duniya sari, tum pe badi zimmedari / Ghar ghar ko tum swarg banana, har aangan ko phulwari, goes a song in the beginning of the film that advises schoolgirls about their future role as married women. We Are Family (2010) observes the dynamics of the three kids of a divorced couple with their father’s girlfriend. It may be separated by decades from Talaq and Mr & Mrs 55, but it isn’t very different in how they perceive their women primarily—as nurturers.

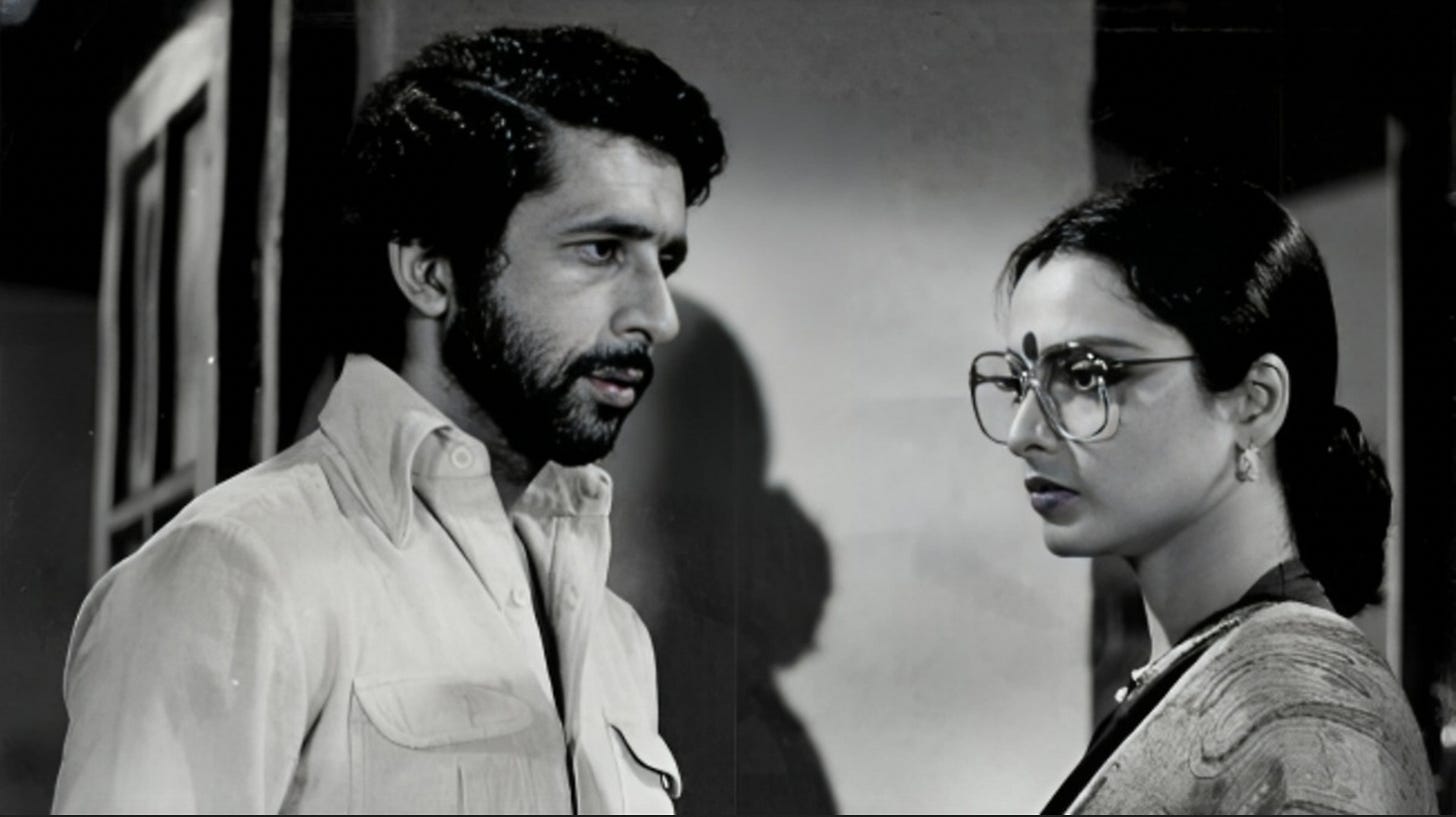

One of the reasons for rancour between the couple in Talaq is the wife’s desire to go back to work. She’s asked to choose between family and a job. This hurts her self-esteem and pushes her marriage to a point of no return. This ultimatum pops up in Hindi cinema almost whenever there’s a depiction of a ‘career-oriented’ married woman. It happens even when women have taken up jobs out of necessity and are then guilted about their absence in their homes. Such narratives have almost always sided with the man’s perspective—regardless of how flawed it is. In Kaash (1987), the alcoholic and out-of-work husband asks his wife to quit her job for no valid reason except his chauvinism. This happens right after he physically assaults her and extends no apology. When she asserts the job is important for her self-worth, she’s asked to leave. Their marriage is over, and the custody battle for their son begins.

Two’s a marriage, three’s a crowd, sang George Jones. Extramarital affairs and their complications have made for some fascinating cinema, though films about adultery have often been more forgiving to men than to women. Unfaithful, repentant husbands are shamed but given second chances. Think Pati Patni Aur Woh (1978), Yeh Nazdeekiyan (1982), Biwi No 1 (1999), or Masti (2004). The list goes on. In contrast, the wives in Dastaan (1972) and Achanak (1973) die for their unfaithfulness. A few notable exceptions, Guide (1965), Rihaee (1988), and Astitva (2000) are where women have called out the male hypocrisy of putting the onus of morality only on them. The most powerful comment on this double standard comes from Arth (1982). In spite of cheating on her and divorcing her, Pooja’s ex-husband hopes she’d accept him when he comes back to her after getting dumped by his lover. “Jo kuch tumne mere saath kiya, agar main wohi tumhaare saath karti aur issi tarah laut ke aati toh kya tum mujhe waapas le lete?” she asks to settle the duplicity once and for all.

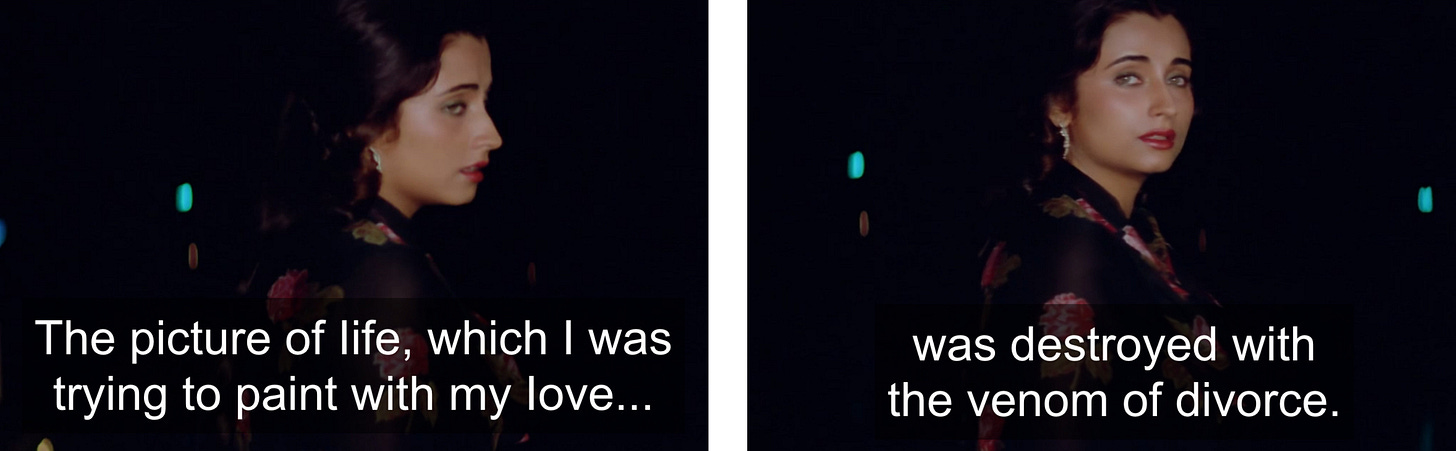

The same year, BR Chopra’s social drama Nikaah was another important film surrounding marriages and divorce. It questioned the male privilege. An educated young Muslim woman, Niloufer is left stunned when her husband, Waseem, whom she had married so lovingly, divorces her in a fit of rage. Overcoming this trauma, she finds love and marital bliss with Haider. When a remorseful Waseem returns to her life, Haider takes it upon himself to reunite the former couple, thinking a woman could never get over her first love. Frustrated with the men around her taking decisions on her behalf, Niloufer explodes at this state of helplessness and humiliation. She points out Haider and Waseem are no different from one another. “Inhone talaq gaali ki tarah di aur aapne tohfe ki tarah.”

Interestingly, during Nikaah’s making, Chopra and the film’s literary advisor, Rahi Masoom Raza, held the ‘aurat ka pehla pyaar’ theory and wanted Niloufer to reunite with Waseem, but writer Achala Nagar stood her ground, maintaining that a woman would choose to be with a respectful and empathetic partner rather than going by the sentimentality of first love. Her reason was supported by Chopra’s son Ravi, also the film’s associate director. Nagar was right. Women appreciated this aspect of the film the most, as she recalled in an interview with Vividh Bharti.

Male entitlement and a woman’s self-respect in a marriage became the premise of 2020 drama Thappad. During a party, Amrita is slapped in the presence of their friends and families by her husband, Vikram, who is furious about losing a promotion. What follows is the shocking indifference and dismissal of her anguish—with no apology and not even an acknowledgement—by him. Everyone around her expects Amrita to forget, forgive, and move on. She doesn’t and files for divorce. Her ‘overreaction’ over a slap packs deeper issues like sexism, patriarchy, and domestic abuse. The information and the access to the legal system and the ability to get out of an abusive marriage are more open for women up in the hierarchy of caste and class. This gets reflected in the film itself, where Sunita, the domestic help in Amrita and Vikram’s house, is seen fending for herself against her physically abusive husband. She has to stand up for herself minus any support or promise of a better future.

For the dreamy world of love, romance, and happily ever after glamourised by Hindi cinema, it has also delved into the struggles and complexities of marriage. Basu Chatterjee’s Priyatama (1977) demonstrates how sometimes simply love is not enough. A madly-in-love young couple struggles with compatibility issues post marriage. The constant bickering and disagreements take a toll on their relationship, verging on divorce. Dum Laga Ke Haisha (2015)—a beloved film from what can be called contemporary middle cinema—reverses the plot. The newlyweds of an arranged match file for divorce, citing incompatibility, only to fall in love along the way. While both films acknowledge the crucial role of family members in mending marriages, it isn’t always true. Kora Kagaz (1974) details how meddlesome families can be detrimental to a marriage even when the partners are level-headed individuals. Years later, when the two meet, do they realise the life they could have had together?

Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975), too, explores an estranged couple’s reconnection. Though not divorced, Aarti and JK go their separate ways after Aarti decides to enter politics. Unlike most films like Do Anjaane (1976) and Apnapan (1977) that make an ambitious woman regret her decision, Aarti isn’t shown as a sorry figure or judged for her choices. Reconciliation happens naturally as both parties understand each other’s perspective. Aandhi doesn’t end with a happily ever after but with a more realistic hint of a reset. An intricate understanding of marital strife and alienation among married couples also came from alternative cinema. Anubhav (1971), Aavishkar (1974), Griha Pravesh (1979), and Saath Saath (1982) explored the cracks and conflicts within a marriage in the most unadorned manner. But what’s interesting is that almost every film, mainstream, middle-road, or arthouse, has been inclined towards reconciliation or indicated it.

The awkwardness around divorce and the difficulty to accept that people can outgrow a relationship or simply be unable to make the marriage work despite their best attempts happen in life. And films are no different. Once again, it’d be Gulzar who offers a mature take on this perspective with a bittersweet Ijaazat (1987). On a rainy night in a railway station waiting room, Sudha and Mahendra run into each other for the first time since their divorce. The wait gives them the time and chance to revisit their past, re-examine their actions, and still move forward. It is done with a kind of quiet affection and dignity that remains peerless in all these years of Hindi cinema storytelling.

(An edited version of this piece was first published in News9 on June 22, 2022.)

Enjoyed the read? Don’t miss out on Flashback Bollywood’s other posts.

All images used on Flashback Bollywood are the property of their respective owners and are used for representational purposes only.